Skill Builders

Article

Redemptive Transparency

On a Sunday in early 2018, I stepped into the pulpit knowing I was taking a serious and potentially costly risk. I was about to share a deeply personal story of my weakness and failure yet a story of God’s grace and redemption. Just days before, I had been told by a seminary professor, whom I greatly respected, that he would never share something like this publicly as there was too much to lose. I was preaching on the power of the gospel to change people and had personally experienced the gospel’s healing power in my own life and marriage.

The previous fall, my marriage had gotten so difficult my wife and I were left with no other option but to seek counseling. As we met with a Christian counselor, I was reminded again and again that the gospel releases us from the burden of performance and living up to expectations, allowing us to live with hope and freedom found in our identity in Christ. It was this gospel encouragement that changed my mindset and thus, my marriage. Our ongoing conflict subsided, and our marriage was healed.

This is what I told my congregation that Sunday in 2018. I told them that I went to counseling, that I had treated my wife poorly, and how I had forgotten the truth of the gospel in my own life by believing it with my mind but not fully accepting it in my heart. I told them that being reminded of the reality of the gospel had revolutionized my relationship with my wife. After the sermon I had many positive and grateful comments from my church body.

Is Vulnerability Negative?

Now this may or may not seem like a controversial decision. However, at the time I felt conflicted in my spirit, even while being confident that the Holy Spirit was prompting this public transparency. I was conflicted because the tribe I grew up in, and the churches I watched my father pastor, did not hold transparency to be a positive but rather a great negative. In fact, public vulnerability and admitting any semblance of weakness was often seen as unbecoming of a leader.

An example of this was when my father worked at a very well-known mega-church as the high school pastor, serving under the leadership of a famous and respected preacher. On occasion, he would fill the pulpit when this pastor was out of town or writing a book. During one of these opportunities to fill the pulpit, my father preached a sermon on Psalm 73 where Asaph speaks to his struggle with temptation and envying wicked people. To illustrate these themes my father shared a very personal story of a time when he faced a real and enticing temptation. His personal story perfectly illustrated the biblical text and deeply resonated with the church body.

However, that next week my father was told to report to the senior pastor’s office. Rather than receiving encouragement and thanks, he was told that he was to never again share a story of such weakness from this man’s pulpit because preachers must present people with a standard to aspire to, not lower themselves to the congregation’s level.

This mentality is echoed by many in evangelicalism, especially in the context of preaching and teaching. This is why I was conflicted regarding transparency and vulnerability. I often wondered, who is right? Should transparency and vulnerability in ministry be viewed as beneficial or detrimental?

This question, the answer for which alluded me for years, became a major focus of study. I read widely about transparency, vulnerability, and self-disclosure in the subjects of leadership, counseling, public speaking, and preaching. What I found was a consistent belief that the sharing of oneself, when done well, can be immensely beneficial as a means of identifying with and forming personal connections with others, a way to build trust and credibility with others, and can be a catalyst for sacrificially helping others by modeling healthy vulnerability for them.

In addition to the reading I did in the aforementioned topics, I also considered what the Bible has to say about this question. My study revealed that the Bible gives us many examples of transparency modeled by biblical leaders and preachers.

Paul Models a Life that Is Vulnerable and Transparent

One of the best examples is the Apostle Paul. Paul wonderfully models a life that is vulnerable and transparent in all the right ways. The kind of transparency and self-disclosure we see in Paul is what Zack Eswine has called, “redemptive transparency.”[1]

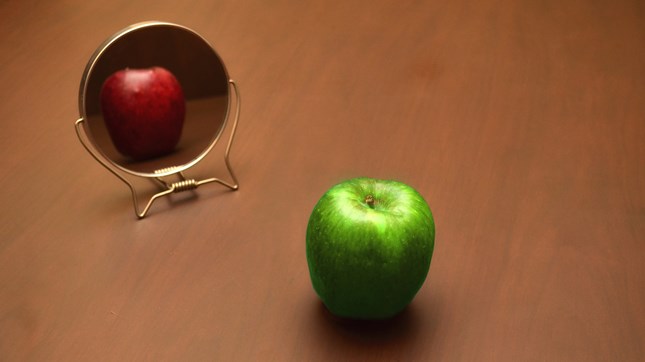

This kind of biblical transparency and vulnerability avoids two negative extremes usually associated with self-disclosure.

The first extreme is a kind of faux perfectionism. No one is perfect. Yet, many try to put on an air of perfectionism which causes them to seem spiritually superior and aloof.

The other extreme is to overshare. Dr. Robert Smith calls this “ecclesiastical nudity.” Brené Brown of TED Talk fame, and a research professor who studies shame, empathy and vulnerability, describes this kind of oversharing as “floodlighting.” Floodlighting is a false transparency, as your self-disclosure forms a kind of shield. This happens when a person gives too much information to someone whom they have not connected with properly, resulting in the other person pulling back like a floodlight was flashed into their eyes. Sharing in this fashion “is blinding, harsh, and unbearable.”[2]

Transparency that avoids either of these negative extremes, and transparency that is truly redemptive, is practiced when the personal weakness of the preacher is wisely revealed with the goal of making much of Jesus and his redemption for the sake of those we lead and teach.

Now, let’s look at some examples of transparency from the Apostle Paul, pointing out specific guidelines from each for the use of redemptive transparency in our preaching.

Paul’s Self-Disclosure of His Conversion (Acts 22 and 26)

The first example comes from comparing Paul’s self-disclosure of his conversion in two different settings.

In chapter 22, Paul has been arrested because of a riot that broke out when someone falsely accused him of bringing Greeks into the Temple complex where Gentiles were forbidden to go. Rather than resisting his arrest, or crying foul, Paul requests the opportunity to address the people directly. He then shares the account of his personal conversion story, emphasizing who he was before Christ, specifically his education and that he persecuted the church (22:3-5), thus identifying himself with the crowd.

Later in chapter 26, Paul is still incarcerated. We see him once again give his testimony to King Agrippa, Bernice, and Governor Festus, but this time he emphasizes a different feature of his conversion. In this instance, he focuses more time on seeing Jesus very much alive, risen from the dead. We see this is a key objection, especially for Governor Festus (26:8, 24). Paul addresses King Agrippa’s personal knowledge of the Jewish Scriptures, and the events surrounding Jesus’ death and resurrection, tying them into his own story for maximum impact.

Let us consider what we can glean from these two different versions of Paul’s personal testimony.

First, redemptive transparency should be tailored to the audience. When we compare and contrast these two accounts, as well as the original story in Acts 9, we see a divergence of details shared in these three versions of Paul’s conversion. While all three are true, they are adapted strategically, the details of which are very intentionally crafted for the audiences.

Next, we see that redemptive transparency can be used to build credibility. Paul used self-disclosure to establish his authority and credibility with those to whom he was speaking. This is true in Paul’s Epistles as well.

We see this clearly in Acts 22, as Paul intentionally reveals the shameful details of his zealous and violent past, thus identifying himself with his audience. In Acts 26, Paul appeals to not only his experience but also to Agrippa’s personal knowledge of aspects of Paul’s account. It is difficult to deny someone else’s personal experience. It is even more difficult to excuse an argument when there is personal knowledge of its veracity.

Finally, redemptive transparency can be used to powerfully proclaim the gospel. Paul used the story of his personal conversion to great effect. There is arguably no greater tool at our disposal than the story of how Christ has changed our hearts and lives. It is a powerful tool when people can hear who we used to be, or who we would be without Christ, and then hear about the new people we are in Christ.

However, salvation is not only what we were delivered from, but also the truth that we are being changed into something and someone new by the power of the Holy Spirit. This means that not only is our initial conversion story significant but also our subsequent and ongoing sanctification stories. It is to Paul’s self-disclosure of his sanctification that we turn to next.

Paul’s Fleshly Frustration (Romans 7:7-8:1)

If you are a church leader you are very familiar with this text. It is both a well-known and debated text.

The main issue of interpretation is identifying when the fleshly frustration Paul describes took place. Is this Paul describing himself before his conversion, as an immature Christian, or in the present?

I believe that no matter which view you hold to, you can learn about redemptive transparency from Paul’s vulnerability. Paul is laying a shameful part of himself (whether past or present) bare for all to see. However, we also see that Paul is very careful and intentional about what exactly he shares.

This is not a case of floodlighting like we talked about earlier. Instead, we learn that redemptive transparency should intentionally balance specificity and ambiguity. As Zack Eswine writes, “Redemptive vulnerability invites preachers to a general transparency with everyone, a specific vulnerability with a few. Paul told us in a generally vulnerable way that he struggled with the sin of covetousness (Rom. 7:7); the details he left unmentioned. Perhaps he shared those with Titus or Timothy.”[3]

Paul’s Resumé (2 Cor. 11:16-12:10)

Finally, we come to a large section where Paul essentially gives the Corinthian church his resumé. He was being compared to those that he calls “super apostles” (v. 5) who would list achievement after achievement to prove that they were worthy to be followed. Paul does not combat the “super-resumés” of these super apostles. Instead, he shares about his weaknesses, sufferings, and personal struggles.

What can we learn from this? Redemptive transparency should reveal the humility and weakness of the preacher while reminding people of the greatness of Christ and his gospel.

Because of the braggadocious church leaders who flaunted their achievements while questioning Paul’s credentials, he had to talk about himself. Yet, what Paul listed as his “achievements” were not his many successes but his suffering and weakness.

He then quickly turned away from himself to speak of the sufficiency of Christ’s grace. Jesus was always the focus and the hero. Proclaiming the gospel was always Paul’s ultimate purpose. Paul never wavered from this.

Conclusion

In each of the passages that we looked at, and in many others, we find that Paul willingly shares much about himself. He shares good things, but he also reveals his past failures and even his present weaknesses and struggles. We know what we know about Paul because Paul allowed himself to be fully known.

Not only that, but because so much of Paul’s own self-disclosure ended up in the New Testament canon, we have to conclude that God intended Paul to be fully known. As Zack Eswine writes, “I likewise hope that those of us more accustomed to a didactic and Pauline approach will remember how often Paul referred to himself and his stories in his letters as well as the fact that we know his personal story and not just his teachings, and this by God’s design.”[4]

There is a piece of artwork called SPEAK featured at Regent College in Vancouver, British Colombia. It was created by local artist David Robinson to represent “the preacher.” The caption explaining the art says,

The preacher hangs inside the pulpit, thin, vulnerable, human. His life is given to preaching God’s Word. He is laid bare before the congregation, bare before God. His life fuses with the service of the pulpit. God’s Word sustains him—God’s Word spoken through him. He is fully aware of his humanness, aware that he is not God, but rather in service to God, and to God’s people. This preacher is aware that his place behind the pulpit is one of cost, humility, of honesty …[5]

This sculpture dramatically demonstrates that preaching often requires laying ourselves bare before God and our people. This is what we see in the Apostle Paul. This is redemptive transparency at its finest. This is the kind of vulnerable self-disclosure that the Bible calls us to practice.

[1] This phrase was used by Zach Eswine to describe the preaching of Charles Spurgeon in Kindled Fire: How the Methods of CH Spurgeon Can Help Your Preaching, Revised edition. (Fearn, Ross-Shire, Scotland: Mentor, 2006), 75–76.

[2] Brené Brown, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead, Reprint edition. (New York, NY: Avery, 2015), 160.

[3] Zack Eswine, Preaching to a Post-Everything World: Crafting Biblical Sermons That Connect with Our Culture (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2008), 90.

[4] Zack Eswine, Sensing Jesus: Life and Ministry as a Human Being, Kindle Edition. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2012), 26.

[5] For a full description of the sculpture go to https://artway.eu/content.php?id=721&lang=en&action=show