Christian Unity and Politics: Why Both Parties Are Wrong

Introduction

My aim in part one of this series was to show how the two truths of baptism—dying with Christ and rising with Christ—correspond to our political impulses. I made the observation that the “dying with Christ” truth of baptism corresponds to a politically conservative impulse, and the “rising with Christ” truth of baptism corresponds to a politically liberal impulse. And the point for Christian unity is that both political impulses—though not always true or right in their application—are rooted in our baptismal truth. Therefore, we need to be generous to each other in the midst of our political diversity.

Broadly speaking, our baptism teaches us to see the good in all things, including politics. But our baptism also teaches us to see the brokenness in all things, including politics. So if last week’s message was about seeing the good in the political impulses of your brother and sister in Christ, this week’s message is about seeing the potential dangers of your own political impulses.

We’re going to return again to Romans 6 and baptism. Not only is the gospel composed of two truths—dying and rising with Christ—but these two truths exist in a particular relationship, or order. I want to observe this relationship, and then look at what happens when we get these two truths out of order—both spiritually in our Christian life, as well as politically. So like part one, the first half of the sermon will look at baptism, the second half will look at politics.

(Read Romans 6:1-8)

Dying and Rising with Christ

I want us to pay attention to a key phrase in verses four and six. Paul is saying the same thing three or four times, in three or four different ways to make his point. Paul says that we were buried “in order” that we might rise, in verse four; and then he says the same thing again in verse six. Our old self was crucified with Christ “in order that” the body of sin might be brought to nothing.

All throughout this passage, Paul is not only asserting that dying and rising with Christ are both essential aspects of the gospel, he’s also asserting that they exist in a proper order, or relationship to each other. We die in order to rise. Dying with Christ is not an end in itself. We don’t die with Christ just to die with Christ. We die with Christ “in order” to rise with Christ. Or we can say it in good Aristotelian fashion: Dying with Christ is a means to achieve the greater end of rising with Christ. Means and ends are not simply two independent goods, both equally worthy in their own right.

Think about tools in a tool box. Means and ends don’t sit side-by-side, like two important but distinct tools in your tool box—like a wrench and a screwdriver. Sometimes you need one, sometimes the other. Rather means and ends fit together like a drill and a drill bit. The drill provides the power and force that enables the drill bit to spin and cut. As such, the drill doesn’t exists as an end in itself; it is a means to a greater end; but just because the drill is a means and not an end doesn’t make the drill unimportant. The drill bit depends upon the drill to accomplish its appointed end. So both the drill and the drill bit are absolutely essential for drilling holes; but they are essential in a particular ordering, or pairing, or relationship.

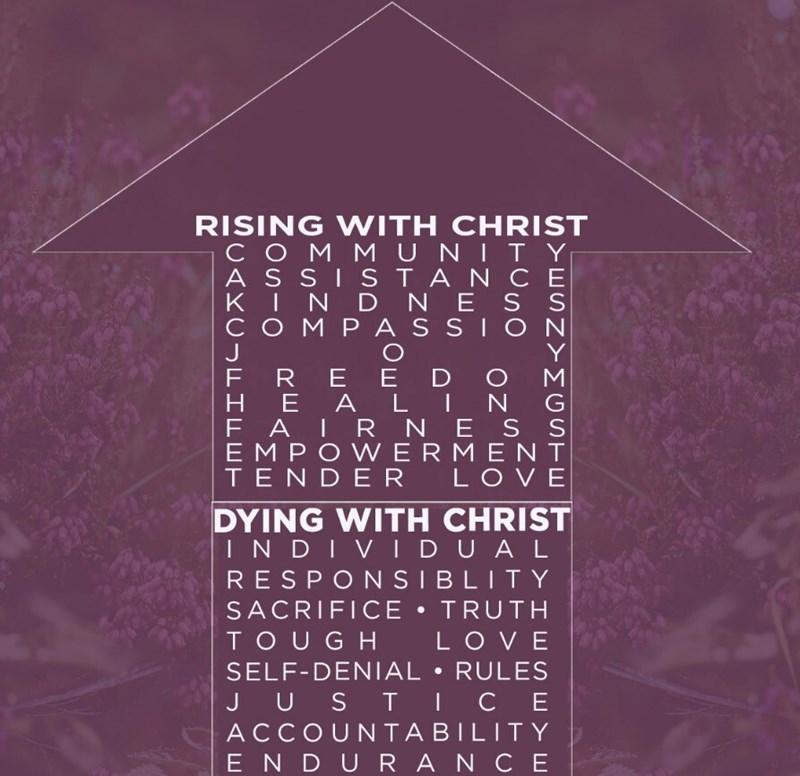

That’s how it is with dying and rising with Christ. The “dying with Christ” impulses of baptism are the essential means that make possible the greater end of our “rising with Christ” impulses. So our baptism doesn’t just teach us there are two gospel impulses. Rather it teaches us that these two impulses fit together in a particular way. Let’s go back to our list from last week that highlighted these two baptismal truths.

Truth, rules, justice, sacrifice, and endurance, all of these “dying with Christ impulses” are valuable as a means. These are all good and necessary, insofar as they are striving toward and enabling the “rising with Christ” impulses of freedom, joy, and so on. We sacrifice for something, we endure for something, we have accountability for something. The dying with Christ impulses are not ends in themselves. They exist for something. What they exist for is the “rising with Christ” impulses.

Coming to terms with the proper relationship between dying and rising with Christ is a knife that cuts in two directions. And I’m going to wield it in both directions. Those of you who tend to prioritize the “dying with Christ” impulse, listen closely—this first cut of the baptismal knife is for you.

Dying with Christ Impulses

Here’s the first cut of the knife—the dying with Christ impulses of our baptism, when they are valued as ends in themselves, rather than as means, when they do not reach for and enable, when they do not serve, the “rising with Christ” impulses become sterile and destructive. What good is truth if it doesn’t lead to kindness? What good are rules if they don’t create a context for flourishing and freedom? What good is justice if it doesn’t create a fair society? What good is denying oneself if it doesn’t ultimately lead to joy? What good is a doctrinally sound church if the sound doctrine doesn’t foster a loving community?

All of the “dying with Christ” impulses are only valuable when they are in service of the “rising with Christ impulses.” We can get ourselves into all kinds of problems if we make dying with Christ and end in itself—as if sacrifice and endurance and self-denial were legitimate ends in themselves. We see a good example in the Gospels of what it looks like when the dying with Christ impulses become ends, rather than means. It looks like the Pharisees.

The Pharisees were the theological and doctrinal gate keepers of Israel. They were all about truth, rules, law, self-denial, justice, sacrifice, responsibility, and accountability. No one more embodied the virtues on the “dying with Christ” list than the Pharisees. But none of it was in service of love.

The Bible doesn’t talk a lot about Jesus’ emotional state; the only two emotions ascribed to Jesus in the Gospels are joy when he is praying, and anger at the Pharisees. And when he’s angry at the Pharisees, it’s on precisely this point—it’s because they have embraced the Law (the rules) as an end, rather than as a means. They have lost sight of the fact that the Law existed in service of love. The Law was meant to set God’s people free, to point them to the hope of a loving, healing, and forgiving God. But the Pharisees had taken the law and turned it in to a burden that oppressed the people.

The Pharisees have embraced the conservative impulse and they’ve turned it into and end, rather than a means. If we look back to Matthew 23 we find a rather famous portion of Scripture. It’s Jesus’ “seven woes” against the scribes and the Pharisees. Let me read the first few verses: “The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat. So you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach. They tie up heavy, cumbersome loads and put them on other people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to lift a finger to move them.”

So the Pharisees took the Law of God and they laid it as a heavy burden upon the people of God. This wasn’t driven by love. So Jesus lays out an invective against the Pharisees. He calls them “sons of hell, serpents, brood of vipers, white-washed tombs, unmarked graves” and at the end he calls down on their heads all the blood of the prophets who been unrighteously killed since the foundations of the world. Honestly, it’s all a bit terrifying. Justice without mercy, truth without kindness, accountability without compassion. No group of people more raised Jesus’ ire than the Pharisees. And it’s because they turned means into ends. They refused to move from Law to Liberty, and instead made the Law an end in and of itself.

Truth, rules, justice, sacrifice, endurance, self-denial, and so forth—when these impulses do not strive toward the greater end of love, they are not just incomplete, they are damnable. Jesus was angry at the Pharisees because they didn’t have love in their hearts. Those of us strong in the “dying with Christ” impulse should tremor at the thought of it.

Rising with Christ Impulses

All right, now let me turn the baptismal knife aim toward all of the “rising with Christ” types. All you rising with Christ folks are like, “Whoot, whoot!—we’re the end toward which the whole things points. I knew we were better than all those joyless dying with Christ people.” Now slow down a bit. It’s true that the rising with Christ impulses are the goal (or end) of the dying with Christ impulses—and so in that sense your native impulses do have a certain priority. But to the same degree that the rising with Christ impulses are the end, or goal of the Christian life, the dying with Christ impulses are the foundation, the ground, the sole means of the rising with Christ impulses.

So look back to our text in Romans 6:4-6—back to our phrase, “in order.” The implication runs in both directions. Just as the rising with Christ impulses are the end of the dying with Christ impulses, so too the rising with Christ impulses can’t exist without the dying with Christ impulses. We can’t rise with Christ except that we’ve first died with Christ. There is no other way to rise with Christ. The entire Epistle of Hebrews was written to make this point. As it says in Hebrews 9:22, without the death of Christ, there can be no salvation; in other words, no rising with Christ.

The dying with Christ impulses are the foundation, the basis, that necessary means that makes possible the rising with Christ impulses. Take the relationship between rules and freedom. You might think rules and freedom are opposites, and that the more rules, the less freedom. But taking away the rules doesn’t get you more freedom, it gets you driving in India. Have you ever driven in India? They are not as particular about the “rules of the road” over there. Very stressful for American drivers, precisely because there are so little fixed rules. Rules don’t get in the way of freedom; rules actually provide freedom. Rules provide the sort of order that is necessary for people to flourish. Trying to enact the rising with Christ impulses, without first embracing the dying with Christ impulses, will get you into all sorts of problems.

So think back to our baptism slide. Kindness that isn’t grounded in truth is mere sentimentality; freedom that is not based upon rules is anarchy; joy that isn’t founded on self-restraint is indulgence; community assistance that isn’t based on individual responsibility is enablement; compassion without accountability, tender love without tough love—both are simply permissiveness. The “rising with Christ” impulses, when not built upon the foundation of “dying with Christ” topple in upon themselves and become destructive. So a better picture of these two impulses is not two lists side by side, but above and below. A better picture of these two impulses, look something like this:

In every case, the “dying with Christ” impulses undergird and support, indeed make possible, the “rising with Christ” impulses. So in summary, both aspects of the gospel need to fit together in their proper order. We die in order to live, and we can’t live without dying. Now let’s turn from here to politics.

Contemporary Politics: There Are No ‘Christian’ Options

I’m not a political historian, and no doubt many of you know more about the history of American politics than I do. But let me begin by making an observation about the evolution of our two political parties, and how things got to their current state. The Democratic Party was founded in the late 1820’s, and the Republican Party was founded in the mid 1850’s. It hasn’t always been the case that the two parties were as politically polarized as they are today. Throughout their history, both parties contained both liberals and conservatives. So for instance, during the mid-1900’s liberal Democrats and liberal Republicans banded together to propose anti-segregation legislation; and conservative Democrats and conservative Republicans banded together to block those attempts.

My point here is not that conservatives are always against racial equality, and liberals are always for it; many conservatives I know are genuinely for racial equality. My point is that in the not too distant past, the two parties were more mixed—having both conservative and liberal impulses in a single party. It wasn’t until the 1970’s and 80’s that our two parties became increasingly more narrow and polarized into their present day conservative and liberal polarities, such that today the Republican Party is virtually synonymous with conservativism, and the Democratic Party is virtually synonymous with liberalism. As a consequence, to engage politically today is to be forced to choose between one impulse or the other. They no longer (perhaps never, really) fit together in a proper ordering. The conservative political impulse is now an end in itself, and the liberal impulse is trying to seek its liberal ideals apart from a conservative foundation. And that, I think, is the chief hurdle for Christians today when it comes to politics.

Just like baptism requires us to hold together a proper relationship between dying and rising with Christ, so too politics work best when a nation’s liberal ideals are built upon a solid foundation of conservative truths. Neither political impulse, taken in isolation, is able to give life. So let me offer a critique of the isolated conservative impulse, and then I’ll offer a critique of the isolated liberal impulse.

Conservative Impulse

The conservative impulse, when not pointing toward the liberal ideal of love, becomes hard edged and oppressive. Let me correct something I said last week. Toward the end of last week’s sermon I commented that both parties have policies and positions that are explicitly anti-Christian—namely pro-abortion on the left, and racism on the right. But that’s wasn’t right. The Republican platform does not have explicitly racist policies; it can’t; that would be illegal (that was the whole point of Civil Rights).

But it’s important for conservatives to bear in mind that the conservative political tradition does not have a great track record on matters of race. Historically, it was the conservative wings of both parties that advocated for segregation—and they continued to do so all the way up until segregation became illegal.

Now please don’t hear me saying that all conservatives are racist, because that’s absolutely not true. My point rather is that the conservative impulse, if divorced from a liberal end, can become racist.

There are no doubt a lot of reasons as to why it’s like this. But here’s my best shot at it. Conservatives care about structure, safety, and security, in the midst of all the potential dangers of the world. Well and good. But when these things are sought as their own ends—when love is forgotten—it becomes safety and security at all costs. The reality is that diversity of all kinds—whether racial diversity, gender diversity, age diversity, or socio-economic diversity—is messy; it can be unruly. It’s so much neater, easier, and safer to be homogenous. The conservative impulse will compel us to retreat away from the danger of diversity into the safety of sameness. So, if the conservative desire for stability, safety, and “law and order” becomes and end in itself, it will tend toward the oppression of diversity.

That was true of the Pharisees. The Pharisees were strongly conservative and strongly racist in their view of the Gentiles. Fraternizing with the Gentiles had led to a break down in Jewish moral order. So they developed a racist attitude toward Gentiles, and as a consequence led many of their fellow Jews into racism along with them.

So if you tend toward the conservative side, especially in politics, be open-eyed that the conservative impulse, when it becomes an end in itself—when it forgets about the higher goals of equality and love—can get quite ugly. When your liberal friends say that they can smell a whiff of racism in the conservative tradition, they’re not making that up—even if it’s not true of every conservative. Don’t let your conservative impulse neglect the higher calling of love.

Liberal Impulse

Liberalism, when not grounded in God’s moral order, does not liberate; it becomes permissive, enabling, and ultimately destructive. American society, driven by the liberal impulses of the 1960’s, sought sexual freedom from the constraints of Christian morality. But “free love” was anything but free. Out of wed lock births, skyrocketing abortion rates during the 60’s and 70’s, an increase of sexually transmitted diseases, and a present day divorce rate of 50%—these have been the price we’ve paid for free love.

We thought that we could find our way to freedom apart from God’s rules, but we’ve only brought the house down on top of us. My point is not that all liberals are immoral, because that’s absolutely not true. My point rather is that the liberal political impulse, if divorced from a conservative foundation, can end up in immorality.

Human beings don’t know how to govern themselves. We need God’s moral order, his divine will as revealed in Christ and Scripture, to know how to build the liberal project of love. When we think we can build a liberal tower of freedom and equality on its own foundation, we end up only building a house that topples in upon itself.

So if you tend toward the liberal impulse, be open-eyed that the liberal impulse, when it ignores a conservative foundation, can get ugly. So when your conservative friends say they can smell a whiff of immorality in the liberal tradition, they’re not making that up—even if it’s not true of every liberal.

For a truly awful example of how devastating the conservative and liberal impulses can become when they are not properly ordered, consider World War II. In World War II, the two most destructive and oppressive leaders were Hitler (the fascist leader of Germany) and Stalin (the communist leader of Russia). Hitler’s fascism was the conservative impulse severed from a liberal end; Stalin’s communism was the liberal impulse severed from a conservative foundation. And between the two of them, they killed millions and millions of their own people and waged a punishing war in Europe that devastated the continent. Their example is a sobering reminder of what happens when the conservative and liberal impulses are severed from each other and not properly ordered.

As the gap between America’s two political parties widens, our capacity as Christians to insert our baptismal impulses into our political system becomes more and more difficult. It’s tough to know what to do in such a position. Imagine for a moment that you were living during the days of WWII, and the outcome between Hitler and Stalin in WWII could have been decided by a vote. Who would you have voted for? It’s an almost impossible question for a Christian to answer.

Now the Republicans are not fascists and the Democrats are not communists (despite what you read on social media). So it’s not as bad as all of that. But tragically, as the polarization and isolation between both parties deepens, we are increasingly put in a position where we can’t vote in a way that holds both baptismal impulses together in their proper order. Do we cast a vote in a conservative direction, even though our vote runs the risk of encouraging the racist impulses of an increasing isolated conservativism? Or do we cast a vote in a liberal direction, even though our vote runs the risk of encouraging the immoral impulse of increasingly isolated liberalism? That’s a tough call, and I don’t fault any Christian for making a different choice than me.

From a biblical framework, our baptism teaches us the unity of God’s truth—that all of life is built around the twin dynamics of dying and rising with Christ. As our two parties move apart, it becomes harder and harder to hold together the unity of God’s truth. Let’s all be aware, and beware, of the dangers that come when we move into a political context that pits one baptismal impulse against the other. In such a polarized context, our choice will be necessarily sub-Christian. So let’s be generous to our Christian brothers and sisters who choose to make the compromises differently than we do.

Conclusion

What American politics is unable to do, the church is both called and empowered to do. Only through Christ are human beings able to truly hold together the right and left impulses of God’s moral order. In our union with Christ in his death and resurrection, we have the ability to move from death to life—from truth to grace, from rules to freedom, from justice to fairness, from sacrifice to empowerment, from endurance to healing, from self-denial to joy, from tough love to tender love.

I was talking with a potential worship pastor candidate about our church, and he noted that one of the things that interested him in our church was our political diversity. He told me that he had been in racially diverse churches, but had never been part of a politically diverse church. In his mind, Calvary’s political diversity is an indicator that we are coming together around something higher than politics. That we are bonded by our loyalty to Christ over and above our loyalty to any political party. And I think he’s right. And what a great witness to our community.

We as a church, insofar as our chief loyalty is to Jesus, have the capacity to show our local community what it means to hold both impulses together. We may not all agree about how best to work out the inevitable compromises that come when we enter into the political arena. But we all do agree that our only hope—the world’s only hope—is ultimately found in Jesus Christ, and that his conservative death has led us into his liberating resurrection.

Let’s strive to continue to be a congregation that leaves genuine room for the political diversity of both left and right—not because political diversity is good in itself; but because churches with political diversity will almost certainly be churches that contain both the left and right baptismal impulses of the gospel. Hebrews 12:2 admonishes us to “fixing our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of faith.” What a good word. Jesus is the author—the foundation, the basis—and he is the perfecter—the embodiment of the ideal end of our faith. In him, he holds together the unity of all reality.

I love you; God loves you; let’s all love each other.

Gerald Hiestand is the senior pastor at Calvary Memorial Church in Oak Park, Illinois, and the cofounder and director of the Center for Pastor Theologians.