Skill Builders

Article

"Setting Words on Fire"

Every leading homiletician is famous for a particular slant on the art of preaching. Haddon Robinson advocates the "big idea." Bryan Chapell looks at the "fallen condition focus." Fred Craddock touts induction. And Eugene Lowry structures sermons with the "homiletical plot." Paul Scott Wilson deserves to be included on the short list of leading homileticians, and his emphasis is on theology, "putting God at the center of the sermon," by preaching from "trouble to grace," a modification of the old law-gospel homiletic. To be sure, other specialists in homiletics are part of the chorus decrying anthropocentric preaching that lacks a vision of God, but Wilson has been leading the chorus for more than a decade.

In Setting Words on Fire, Wilson wants to set sermons on fire by encouraging and equipping us to proclaim and not simply teach. Without a doubt, teaching is vital, but when it does not lead to proclamation, it is like a car fuelled and ready to roll but parked in the driveway. In Wilson's parlance, teaching explains doctrine and its implications for Christian living, while proclamation kindles faith. Here's a comparison:

| Teaching + | Proclamation | = Preaching |

| Talks about the Gospel | Offers the Gospel | |

| Hearing about God | Encountered by God | |

| Commentary on the Text | Personal Address from God | |

| Didactic | Prophetic | |

| Rational | Emotionally Charged | |

| Plain Style | Middle and Grand Style | |

| "Sin separates us from God." | "You have sinned." | |

| "Forgiveness is possible." | "I [God] forgive you." | |

| "Christ's resurrection brings hope." | "In Christ, you can start anew." |

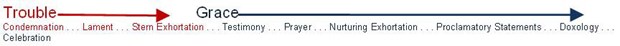

When the flint of teaching strikes the steel of proclamation, God sets our words on fire to produce conviction, repentance, lament, prayer, comfort, praise, hope, celebration, and so forth. Wilson's theory of preaching is grounded in theology, for God's words are creative forces ("Let there be light, and there was light"), as well as rhetorical theory, for words are not mere markers substituting for things, they are speech-acts with performative, or illocutionary, force. Wilson explores nine "subforms," or genres, of proclamation, showing how words do things. The nine subforms range from trouble to grace, from the most dire to the most exuberant:

Setting Words on Fire ranges far over the landscape of scholarship, but the final stop is always praxis. This is one of the reasons I appreciate Wilson's writings. He speaks as a practitioner who wants to renew the ailing Church through preaching (Note: Wilson's context is primarily the mainline church in North America). To equip readers, he advocates imitation, an ancient and honorable method of learning, presenting scores of sermon excerpts from Chrysostom, Augustine, Wesley, and dozens of other preachers. An audio CD accompanies the book with readings that illustrate all nine subforms.

Wilson's heartfelt, well organized, and original theory of homiletics would be even stronger if he had a more consistent view of authorial intent that sees the intentions of the human author as unified with the intentions of the Divine Author. Wilson implies that the intention of the human author is dispensable as we sift the grist of the text to hear the voice of God. Hearing that voice depends mainly on the reader's response to the text (guided by rigorous study), but as I say, his stance is not entirely consistent. While Wilson is thoroughly convinced that "meanings are not limited to authorial intent and include what the words generate in the eyes and experience of the beholder" (29), he also warns about "unwarranted speculation on the text" (47). He assumes that "in our postmodern era, preachers understand that biblical texts have as many meanings as there are perspectives we bring to them" (50), but sometimes he muddies the water by affirming that "the Bible accounts must be allowed to speak for themselves as much as possible" (64).

For Wilson, letting the Bible speak for itself is especially crucial when it comes to the accounts of Jesus' resurrection. Wilson wants us to believe what the authors plainly wrote, that Jesus rose bodily. He challenges theologically liberal colleagues by quoting with approval Luke Timothy Johnson, "It makes a great deal of difference whether you believe someone is alive or dead" (253).

In the final analysis, Setting Words on Fire will help you put God at the center of the sermon and thus, through the Spirit, teach and proclaim with power.

Jeffrey Arthur is professor of preaching and communication at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.