Skill Builders

Article

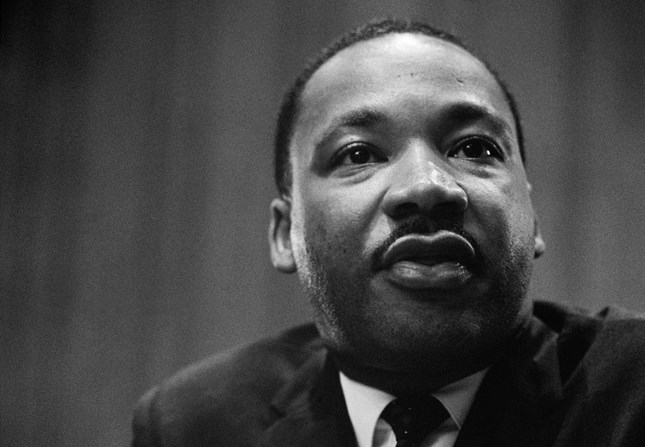

How Has Dr. King Impacted Your Preaching?

Note from PreachingToday.com: We recently posted a previously unpublished Martin Luther King Jr. sermon called "Guidelines for a Constructive Church." So, we asked a handful of preachers the following question: What aspect of Dr. King's life and work has had the greatest impact on your role as a pastor and preacher? In this article we feature answers to that question from Dr. George C. Waddles, Rev. Bryan Loritts, and Pastor John Ortberg.

Speaking Truth to Power

Dr. George W. Waddles, Sr.

Dr. King was known as a champion for justice, a powerful herald of God's truth, and one who was not afraid to speak truth to power. And he was committed to academic preparation. I am deeply sensitive to the need for strong education and being equipped with the knowledge of how to examine God's Word before one engages preaching and ministry.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was also a skilled orator. His mastery of the English language and his spiritual cadence as he preached God's Word and lectured still resounds in my heart today. His well-developed speaking and sermonic style highlights the importance of being clearly understood by the congregation or audience.

But perhaps the most important way in which his ministry and preaching have impacted my ministry is that through his example I learned to be bold, courageous and compassionate to speak biblical truth regardless of the consequences. His example helped to shape my approach to preaching and ministry as one that is not bought off by modern day Pharaohs and Herods, nor enamored with celebrities and people of influence who suggest that we quietly avoid controversial subjects that may offend our contemporary society.

It would have been easy in his day to quietly sit back and allow the hands of time to whittle away—ever so slowly—at the shackles of Jim Crow. There were many who suggested that it was just a matter of time before all things would be equal. I am sure that every day he battled the urge to quit. The odds against him must have seemed insurmountable. But there was an inner fortitude, a strength that was buttressed by the truths of God's Word that kept him.

Through his life we saw the incredible power of God's Word at work. His Six Principles of Nonviolent Resistance were not some philosophical musings. They were solidly anchored in the truths of God's Word, much of which is found in Jesus' teaching in Matthew, chapters 5-7. And it was the power of his Word at work that brought change—for a people, and for a country.

I am convinced that the survival of the church in America depends on this one truth: God's Word is still true. It has been my privilege to labor as a pastor for almost forty years preaching God's Word and encouraging others in proper exegesis and application. My heart has been grieved by the efforts of the enemy of our souls to move God's people away from biblical truth to a feel-good, consumerism that constitutes easy believism. Others choose to interpret scripture through a cultural, ethnic lens that does great damage to the biblical text.

There is perhaps no place where God's Word is assaulted more visibly than in the reality of the church in America. Like Dr. King, I passionately desire to see the day when we will no longer be satisfied with the status quo brand of Christianity, but based on Jesus' teaching we will become literally "one body in Christ Jesus." The barriers we've established, the walls we've erected, the exclusions we've practiced, and the segregationist racism that has infected Christianity—all gone. I join my voice with Dr King's voice in declaring that it's not only unjust, it is unbiblical and un-Christian. But this cannot, and will not happen until God's Word is restored to its place of honor in our churches and in our hearts.

To that end, it is mine to continue to declare boldly the truth of God's Word. To add my voice to the chorus of that drum major for justice declaring: "Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord. He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored. He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword, His truth is marching on." His truth still stands.

Dr. Waddles is the Pastor of the Zion Hill Missionary Baptist in Chicago, Illinois and the Founder and President of Biblical Exposition Conference.

Preaching a Cross-Shaped Gospel

Rev. Bryan Loritts

In 1954, Ray Charles shocked the world with his release of, I Got a Woman. The response to this song was polarizing. Some hailed Charles to be a musical genius while others condemned him to hell. At issue was the inspiration for Charles' classic, which came from an old gospel song, It Must Be Jesus. With a flash of a pen, Ray Charles had contorted this Christian hit into an opus that would make those in the church house blush. Yet however one viewed Ray Charles' pending eternal state, what cannot be denied is that Ray Charles was a musical genius who defied labels. His ability to sing gospel, country, R&B, and to even "mash up" these seemingly hostile genres into a chart-topping hit was unparalleled. Ray Charles was the epitome of versatility, which was the key to his musical immortality.

Around the same time Ray Charles was stirring up trouble, his contemporary, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was scaling his own mountain of immortality. While their stages were different, both Ray Charles and Dr. King shared the virtue of versatility. Like Ray, Dr. King refused to be labeled as one thing. He was neither just a preacher, nor just a civil rights activist. He was both. King's understanding of the gospel propelled him to preach in the pulpits of our churches, and to march in the hostile streets of our nation.

Fundamental to the gospel message is the "mash up" of the vertical with the horizontal, the spiritual with the sociological. To follow Christ is to be reconciled to God through the sacrificial, atoning work of Jesus on the cross. And yet following Christ also means to love our neighbor as ourselves. The gospel is both vertical and horizontal.

Metaphors and verses abound in the Scriptures, tethering these two foundational pieces of the Christian life together. This is exactly what I explore in my book, A Cross Shaped Gospel. The very shape of the cross is an illuminating metaphor of what it means to follow Jesus. The vertical beam connects us to God, and yet the horizontal beam propels us to embrace one another. With the cross you cannot have one without the other. While love for one's neighbor is not necessary to be saved, it is the necessary fruit that Christ has indeed stepped into and invaded a life (John 13:34-35).

Jesus taught that the great commandment was both spiritual and social, vertical and horizontal; for we are to love God (vertical) with the totality of our being, and our neighbor (horizontal) as ourselves. The apostle John wondered aloud how it could be possible for a person to love God whom he has not seen (vertical) while hating his brother whom he does see (horizontal). Paul's epistles usually follow the format of what we should know about God, and then how we should incarnate this knowledge among others.

A seminal place where one finds the connection of the vertical and the horizontal is Ephesians 2. In the opening ten verses we see the richness of salvation, how God saved us when we were dead in our trespasses and sins. Paul tells us that we have been saved by God's grace through faith, and that now we are called to walk in good works which God created in advance for us to do. What then are these good works? Keep reading and you'll discover beginning in verse eleven that because of what Christ accomplished for us on the cross the dividing wall of hostility has been abolished and now Jew and Gentile have been united into one new man, worshipping God together in spite of their ethnic differences. Ephesians chapter 2 begins with the vertical dimensions of salvation and then cascades into the horizontal joyful obligations of salvation. Paul wants us to know that to follow Christ requires a versatility in which we actively love, serve and pursue both God and his glorious bride, our brothers and sisters in Christ.

Sadly, Dr. King's commitment to preach and to practice, to exhort and embrace was an anomaly. One of the saddest commentaries of the Civil Rights Movement is that it revealed a schism among those who claimed to follow Jesus Christ. Its biggest opponents were ironically "Jesus-loving Christians" who were content to listen to well manicured homiletical masterpieces while black bodies hung like strange fruit a nine iron away from their churches. On the other hand, some of the biggest advocates for the movement made the error of detaching love for one's neighbor from the biblical moorings of truth.

Dr. King was not perfect, but what he has bequeathed to me as I pastor in the city in which he was slain is a robust and versatile theology that refuses to be labeled as just Ephesians 2:1-10 or Ephesians 2:11-22, but demands to play all of the glorious keys in that chapter and the Bible. Dr. King gave me a theology that demands preaching in the pulpit and practicing in society: a theology that loves God and serves the underserved.

Rev. Bryan Loritts is the Senior Pastor of Fellowship Memphis in Memphis, Tennessee and the Editor of Letters to a Birmingham Jail (Moody Publishers, April 2014)

Paying the Price for "the Dream"

Pastor John Ortberg

The most important, most memorable, and highest-impact sermon of the 20th century wasn't a sermon. At least it wasn't delivered from a pulpit—or a table, music stand, or Plexiglas lectern.

It was delivered outdoors, at the center of political power, in a non-church setting, to a congregation that would never gather again. And it has become an icon of the human conscience; a picture of shalom that has seared its way into the conscience of America.

When I think about Martin Luther King, Jr., one of the first questions that occurs to me is why I was not more impacted by him in the church where I grew up. I was, like him, raised a Baptist, with a keen interest in the church and in the ways that God has valued humanity. However, I don't ever remember him being cited or discussed, even though I grew up in the years of his greatest impact, and was just ready to enter adolescence when he was assassinated.

Why is it, I wonder, that in the 18 and 19th centuries many of the greatest voices that spoke against racial injustice were voices of evangelical faith like John Wesley, Charles Finney, and Jonathon Blanchard—while in the 20th century evangelical voices were too often conspicuously silent in the life and movement that Martin Luther King, Jr incarnated?

A few months ago, I showed our congregation a slice of a racial map of the U.S. Different ethnic groups are represented by different colored dots—one dot for each of the three million plus residents of our country. In the area where I live, the variety of colors is prolific. In the city where I grew up, a river ran through it. Most dots of one color lived on the east side; most dots of another color lived on the west side. At birth, those dots on the west side faced a life where their opportunities and resources and safety would be far less than the dots on the east side. But I don't remember talking about this as a church.

When I was a little boy, we used to sing a song about the dots: "Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight." But for some reason, when the dots grew up, we didn't sing that song much. We didn't talk about what the implication might be of each dot being precious in his sight.

Martin Luther King, Jr. talked about the dots. He was both blessed and cursed with what W. E. B. Dubois called "double vision"—the capacity which visited African-Americans with the ability to see both what America claimed to be and what it actually was. Part of what sin does is to blind, and those who are particular victims of such sin can see it more clearly than those who may benefit from it.

Dr. King has other ways of informing those of us who preach as well. There is a wonderful passage in Taylor Branch's Parting the Water that tells the story of King's iconic talk. He had been speaking from a prepared manuscript that focused mostly on the image of a check that had been written but not yet cashed by a nation committed to justice but riddled by racism. At one point he quoted from the prophets about the coming of justice, and the crowd began to call out to him: Yes, tell it. Not so much like the kind of church crowds I grew up with. This was the kind of crowd that answers you back.

From behind him, someone (it may have been the great soprano Mahalia Jackson) called out, "Tell them about the dream, Martin."

So it began.

He had spoken about the image of a dream before. It was a riff; a great blues riff, that drew art and truth and prophetic together in the way that people sometimes pursue and God sometimes enables. And the moment and the man and the Spirit met together, and the conscience of a nation was touched, and our national vocabulary is different today than it would otherwise have been. For the dream was not just his dream; it was the dream of shalom; the dream of a community in which "the dividing wall of hostility" was broken down.

One of the challenges that Dr. King as a preacher leaves for every preacher is his capacity to take the best of thought and scholarship and make it accessible to the least educated listener; to do what Garrison Keillor called putting the hay down where the goats can get it. MLK himself was highly educated, and received a PhD from Boston University while working full time at a church and helping to lead the growing Civil Rights Movement. But he placed himself under the rigorous discipline of taking lofty or complex thoughts and boiling them down into words that every listener could understand and love.

Human rights and dignity can involve complex foundations. But he spoke of "somebodiness," how the poorest or most forgotten human being still possesses "somebodiness," that there's something in every human heart that cries out: "I am somebody and not nobody." And nobody could fail to get it.

He challenges yet more deeply. He called people to pay a great price. He recognized fully that he himself might be called to pay that price. He gave up comfort and safety; he was hated by some and misunderstood by others. He spoke with a moral and spiritual authority that comes only with sacrifice and suffering.

And so we listen still. And so we learn.

John Ortberg is pastor of Menlo Park Presbyterian Church in Menlo Park, California and the author of Who Is This Man? and The Me I Want to Be.