Skill Builders

Article

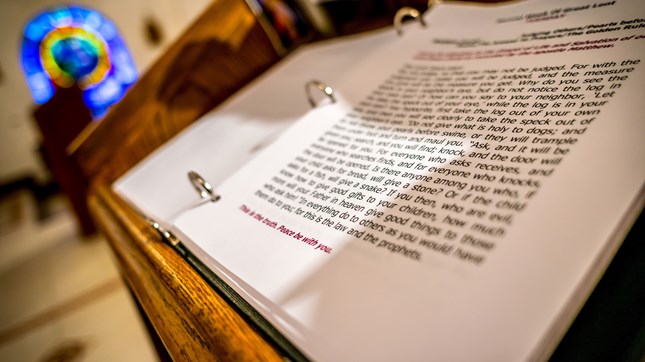

Persuasion in Preaching

A sermon is a persuasive speech. The kind you learned about in high school speech class. Preachers persuade people to respond to God's Word. Persuasion is necessary because all Scripture is counter-intuitive to the minds, emotions, and wills of the world's lied-to people. Preachers bend their persuasion toward the Bible's stated benefits: "teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness."

Persuasion requires skill. Did you hear about the preacher who would occasionally write in the margin of his notes "PWSL," which stood for "Point Weak, Shout Louder"? It would be a shame if that's all we knew about persuasive preaching. Some preachers feel that the mere stating of biblical truth is persuasion enough. One of my professors, Dr. Warren Wiersbe, warned us against ending sermons with, "Now may the Lord apply his Word to your heart." As if to say, "I'll give you the facts. You figure out what to do with them."

Aristotle identified three classic elements of persuasive rhetoric: ethos—the credibility of the speaker, logos—the assertions and arguments, and pathos—the emotional appeal. To care about these rhetorical elements is to care about your listeners—to honor what they need to change.

Ethos

A preacher's ethos requires that we practice what we preach. Authenticity and godliness count for more than we realize. The church I serve is a mile from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. I preach to godly, world-class scholars as well as new believers. It can be intimidating. A few weeks before my first Sunday I remember hearing on the radio the man who was filling the pulpit till I arrived. Preaching on national radio! How am I supposed to compete with that? I thought. To which God replied, "You are their pastor. They'll listen to you."

The extraordinary advantage preachers have over all other speechmakers is the Holy Spirit. He invigorates our sermons, as every gospel preacher knows. But for the Spirit to speak clearly and freely through us we must pray well. It is essential to our ethos. At every stage of preparation we pray. We listen. We lean into our sermon questions by asking God for clarity. We let the text's physician fingers prod our hearts to see if all is healthy. Prayer synchs our preaching with the Holy Spirit. Prayer makes sure we're on the same page with him. When that happens, the sermon is persuasive.

When it comes to credibility we have another advantage. When we preach God's Word to God's people they resonate with what they hear. It rings true. These heaven-bound pilgrims hear in our sermons the accents of their mother tongue and they want to believe what we say. Most of the time our listeners are on our side.

Finally, beware of the preacher's shellac, that hard, shiny coating we swab over sermons sometimes. We put on our preacher voice with its practiced earnestness and authority. But we've become actors rather than preachers. In time, though your people might not quite know why, you will no longer be credible.

Logos

Our logos is Jesus Christ and the Scriptures which reveal the Triune God. No speechmaker could ever hope for a better Word, for richer themes, for higher calls to change. But hundreds of preachers forget that the persuasive power in our sermons come from the Word of God, not from our personalities, stories, humor, wordsmithing, or vulnerability. If holiness is our goal (it is, isn't it?) then be sure that Scripture always persuades hearts toward holiness.

Persuasive sermons start with a preacher alone, listening to what the text wants to say and how the Holy Spirit wants us to reiterate it. The closer we get to the meaning and tone of the text, to what it said in the first place, the more persuasive it is. It really is that simple. Persuasive power waits tightly coiled in the Bible passage. We are called to release it. Making the passage say something it wasn't prepared to say saps its strength.

I'm committed to expository preaching because I think that walking a passage's own path to the principle is more persuasive than simply cutting to the bottom line and telling them the principle only. A bonus is that our listeners gradually learn to think in biblical patterns—what I call truth trails.

That said, we expositors shoot ourselves in the foot sometimes. When it comes to persuading God's people, expositors have a bad habit of asking the text to talk too much, of thinking that all the interesting details of a passage lend to the power of the sermon. We end up with an informational speech, but it isn't very persuasive. A sermon is more than teaching. It is persuading!

Here are ways to strengthen your content:

- Your sermon introduction positions listeners to see what you want them to see, the way you direct someone who is blindfolded to stand in just the right place before you show them the surprise. Figure out where a person's natural resistance to this text lies. Where was it for you? Is it a meaty idea for people who'd prefer milk? A duty too easy to disregard? A grace people have trouble believing? To put it another way, what do you need to persuade them of? Write it down and make sure you don't forget it by the time you're finished.

- Contrary to what you were probably taught in Homiletics 101, you don't always have to state the thesis of the sermon at the beginning. Some texts, especially narratives, build toward a point, so preach along those lines of development. Don't spill the beans! Build to the point instead of away from it. The sermon's punch line might come more powerfully at the end.

- Be sure the logic of your sermon is clear. Disorganized sermons are like diluted truth serum. They don't change much. Logos calls for logic. Our rabbit trail asides and rambling stories are not harmless.

- Well-chosen language is powerful. Clichés dull a point. Think carefully and specifically about exactly what you're going to say. Most of us aren't all that good at thinking on our feet. It's fine to speak extemporaneously if you have worked well on words ahead of time. Then they'll come to you naturally. Mark Twain famously said, "The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug." Preachers, unloading so many words as we do, must choose words that have some serious electricity in them.

- Illustrations are not extraneous. They are powerful persuaders. But they must be on point, tightly told, and accurate. Adding them takes time and thought. Use the wonderful database in PreachingToday.com.

- Conclusions do not only sum up. In fact, maybe you don't need to sum up at all if your development has been clear. The main reason for a good conclusion is to bring your persuasion to their hearts. Instead of writing "Conclusion" in your sermon notes, write "So …"

Pathos

Sermons need a certain passion. Maybe Jonathan Edwards could get away with reading powerful sermons in a pinched monotone, but you and I probably can't. But just shouting louder doesn't work very well either. To prepare for pathos—for emotion—is not disingenuous. It is not fakery. It is good rhetoric.

To begin with, every passage of Scripture has an emotional tone. Part of our exegesis is determining that tone. I remember as a boy being required to memorize and quote Lincoln's Gettysburg Address: "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation …" I had never before spoken such words aloud—such lyrical words, words rising above common vernacular to reach for great ideas. I felt myself ennobled just by reciting them. I found myself trying to match the march and timbre of Lincoln. I realized I needed to know what the words meant that day a hundred years earlier if I was to draw anyone to them now. It was probably too much for a schoolboy, but it was great preparation for a preacher.

Have you ever memorized and quoted your text? For most of us it may not be practical very often, but doing so tends to force us to employ the actor's art of embodying the printed word. At least read your text aloud to yourself. How would Moses have sounded telling the Exodus story? What emotion and pacing would David had brought to his psalms? How did Jesus sound speaking the story of the prodigal son? If Paul had preached Galatians instead of writing it I bet he would have pounded the pulpit! To bring your passage's voice to your sermon is to be more persuasive. Tone deaf sermons are about as winning as tone deaf singers.

I've learned from African-American preachers to be bold with passion. Have you listened to Dr. S. M. Lockridge's holy riff, "That's My King"? (If not, stop right here and go listen on YouTube.) He was a man who was not afraid to be more dramatic on the platform than he would be in conversation. I don't know this for a fact, but I'm pretty sure Dr. Lockridge wrote that out and practiced it. He listened to the rhythm of his words. He thought about the poetry, pauses, and pacing. He dared to crescendo to a triple forte. On YouTube someone imagined his words would be even more powerful with images and typography, but I wish they just had him on video. A preacher—alone on a platform but for God—doesn't really need background music or PowerPoint slides if he or she is prepared, passionate, and bold.

Nothing is more important to pathos—to the emotional persuasion of a sermon—than authenticity. When our hearts are molded by our texts, when our emotions are tuned to the pitch of a passage, and when our hearts are Spirit-purified and Spirit-breathing, then emotion will not be manipulative. We will be neither too stoic nor too sappy. We will be moving.

Acts 18:4 says that when Paul went to Corinth, "Every Sabbath he reasoned [debated] in the synagogue, trying to persuade [convince] Jews and Greeks." It is what preachers do.

Lee Eclov recently retired after 40 years of local pastoral ministry and now focuses on ministry among pastors. He writes a weekly devotional for preachers on Preaching Today.