Skill Builders

Article

The Homiletic Incline

“What’s the difference between textual and expository preaching?” It’s one of my students’ most frequently asked questions.

The subject came up again the other day during a conversation I had with a seminary professor. We agreed that the fundamental distinction between textual and expository preaching is one that’s routinely overlooked by students and their instructors alike.

The tendency for most of us, especially as novice preachers, is to look for that difference in terms of a sermon’s arrangement, style, genre, length of Scripture on which it’s based, or the methods by which it’s developed. In truth, none of those variables is the determinative factor. Whether a sermon is arranged deductively, inductively, or in some combination of the two; whether it’s delivered in a poetic, prosaic, prophetic, or parabolic style; whether it’s drawn from Law, Narrative, Wisdom, Prophecy, Gospel, Epistle, or Apocalyptic Literature; be it as short as a one-verse proverb or as long as an entire epistle, none of these things make a sermon to be either textual or expository.

The actual distinguishing trait is something far simpler and more basic. Before we come to it, let’s take a step back in time.

Hazy Concept

For nearly a century, aspiring young preachers cut their homiletic teeth on John A. Broadus’ classic Treatise on the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons. So great has that book’s influence proven to be that many preachers today who’ve never read it, much less heard of its author, still understand there to be three “species” (to use Broadus’ term) of sermons—topical, textual, and expository.

Broadus found it easy enough to distinguish the topical species from the rest but not the other two from one another. Going back recently and rereading what he wrote on how expository preaching compares to textual preaching, I thought I caught a hint of his personal dissatisfaction with his descriptions and was at once reminded again of my own frustrations from many years ago when I first read them.

Whenever I try to put Broadus’ conception of textual preaching into my own words, it’s like trying to pick up an ice chip from off a tile floor. About the time I feel I have it in my grasp, the concept melts away from my touch. To riff off something another great homiletician once said, the mist in Broadus’ book creates a fog in my brain when it comes to this particular subject. Therefore, it brought me no small comfort to read his admission that “there is no broad line of division between expository preaching and the common methods, but … one may pass by almost insensible gradations from textual to expository sermons” (p. 266).

Still, I believe there is a real difference between the three species of sermons identified by Broadus. Recoginzing those differences is essential for an aspiring expository preacher.

Clarifying Question

Part of the reason for both Broadus’ and our own confusion regarding what distinguishes expository preaching from the other two types has to do with our shared failure to appreciate fully the determinative role that authorial intent plays in the exegetical task which precedes the homiletical.

Consider the six brief rules Broadus gave for interpreting a text: 1) interpret grammatically; 2) interpret logically; 3) interpret historically; 4) interpret figuratively; 5) interpret allegorically, where that is clearly proper; and 6) interpret in accordance with, and not contrary to, the general teachings of Scripture. Under rule three, he spoke to the necessity of accounting for an author’s aims when trying to interpret the composition. To be sure, establishing a text’s historical context informs one’s understanding of that text’s authorial intent. But there is more to ascertaining intent than acquainting oneself with a text’s historical occasion. One must also consider what visceral impact the writer wanted their words to have upon their readers, how they arranged their words to achieve that impact, and what outcomes they wanted their words to realize in and through their audience.

For our present purpose of trying to differentiate textual from expository preaching, it will help if we begin by thinking of each book of the Bible not in terms of chapters and verses but as a collection of major themes constituted of developmental thoughts that have been threaded together to deliver one or more thrusts. An expository sermon’s subject, substance, structure, and spirit are all derived from these textual components (see: David L. Allen, “Preparing a Text-Driven Sermon,” in Text-Driven Preaching: God’s Word at the Heart of Every Sermon, p. 133). Topical sermons take only their subject or part of their substance from a text(s). Textual sermons take their structure and either their essential substance or their spirit from a text(s), but never both. Expository sermons take all of a text’s components into consideration.

To put it differently, Haddon Robinson hit the nail squarely on the head when he wrote, “Expository preaching at its core is more a philosophy than a method. Whether we can be called expositors starts with our purpose and with our honest answer to the question: ‘Do you, as a preacher, endeavor to bend your thought to the Scriptures, or do you use the Scriptures to support your thought?’” (Haddon W. Robinson, Biblical Preaching: The Development and Delivery of Expository Messages, p. 5). The extent to which a sermon is bent to match the text is to that same extent expository.

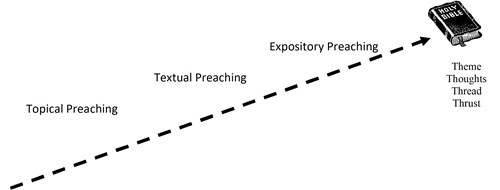

The difference between textual and expository preaching, as well as their difference with topical preaching, is one of gradation. That is to say, we shouldn’t think of these three types of sermons as distinct categories with rigid boundaries separating one type from the other but as ranges on a homiletic incline.

The Homiletic Incline

Imagine an incline. At the peak is God’s written word, consisting of a collection of themes, threaded thoughts, and intended thrusts.

Now, let’s plot in three regions—lower, middle, and upper—and label them topical preaching, textual preaching, and expository preaching. The final product might look something like this.

You will notice that sermons become more biblical the farther they move up the incline. That is to say, sermons become increasingly expository as their preachers shape them to match the theme, thoughts, thread, and thrust of one or more selected texts. Because the topical preaching range lay farthest from the expository, it’s easier for us to distinguish the two. That’s not the case with the textual range, which is so close to the expository that we can pass from one range to the other almost imperceptibly.

Two Types of Topical Sermons

Within each preaching range there are generally two varieties of sermons. In the topical range there are what we might call topical exploratory sermons and topical expository sermons. The exploratory variety is situated on the lower end of the range. It’s this type of topical preaching that Broadus had in mind when he described those sermons in which the text is only the starting-point or motto with which the rest of the sermon has no formal or vital connection (p. 255). The sermon’s theme is only loosely related to that of its text, and its preacher develops that theme according to their own tastes.

Topical expository sermons occupy a higher place in the bottom range. The theme of a sermon here matches precisely the theme of the texts (note the plural) on which the sermon is based. After identifying a theme for their sermon, the preacher searches the Bible for texts directly related to that theme, categorizes them according to which aspects of the theme they develop, decides whether to treat all those aspects in a single sermon or focus on only one, then finishes preparing the sermon accordingly. Practitioners refer to this type of preaching as “verse-with-verse,” as opposed to “verse-by-verse” exposition.

Two Types of Textual Sermons

In the textual range are those sermons that alter a text’s thrust and sermons that augment a text’s thoughts. The altered variety respects a single text’s theme, thoughts, and thread but not its intended thrust. Instead, the sermon applies the text’s contents in a way that falls outside what a fair reading of the text would allow. Sometimes preachers do this intentionally, as when they deliver a sermon on how to get along with one’s mother-in-law based on principles drawn from the Book of Ruth. More often, they do it unintentionally because they fail to see how all their text’s parts fit together to communicate one big idea. They end up taking a piece of that idea then viewing and preaching their text through that particular prism.

Augmented textual sermons respect a single text’s theme, thoughts, thread, and thrust but don’t confine themselves to that text alone. They spend significant amounts of time turning to other passages and filling out more fully what the sermon’s primary text passes over with little development. A sermon based on Micah 6:8 that develops what it means to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with God by exploring numerous verses outside of Micah would be one example.

Two Types of Expository Sermons

In the expository range are what might be termed exegetical sermons and “oratorical” (again using Broadus’ term) sermons. Both varieties respect a single text’s theme, thoughts, thread, and thrust. The exegetical variety exhausts more of a text’s details, but it invariably fails to convey, much less elicit, the text’s emotional thrust as does the oratorical variety. The exegetical expository sermon focuses on the long ago and far away, speaks in third person and past tense, and emphasizes information over persuasion and motivation.

The oratorical expository sermon focuses on the present against the backdrop of the past, speaks in first and second persons and present tense, and emphasizes persuasion and motivation based on information. The exegetical variety is designed for the head; the oratorical variety for the head and heart.

Conclusion

In sum, a topical sermon generally takes less content from a single text than does a textual sermon. Textual sermons take less than do expository sermons. Any given sermon may combine traits from all three classes, but the traits of one class will usually dominate.

An expository sermon, for example, may contain a point, or move, that raises a subject then explores it like a topical sermon by presenting what other passages of Scripture say about that subject. A textual sermon may contain an expository section before moving once again in a textual trajectory.

This is why I say, agreeing with Broadus, that there are no rigid boundaries here but gradations and, agreeing with Robinson, that the overarching question is how faithfully am I presenting this text(s) as the author(s) intended?

It’s both revealing and fitting that Robinson titled his widely used textbook not Expository Preaching but Biblical Preaching. The more faithfully a sermon expounds its selected text(s), the more biblical it is. Anything less is a gradation.

Editor’s Note: A fuller development of this and other answers to the beginning preacher’s most frequently asked questions may be found in Gregory K. Hollifield’s book, Preaching in Red and Yellow, Black and White: Culturally Sensitive Answers to the Beginning Preacher’s Most Basic Questions (2021).

Gregory Hollifield is the Associate Dean at Memphis College of Urban and Theological Studies at Union University and Book Reviews Editor for the Journal of the Evangelical Homiletics Society.