Skill Builders

Article

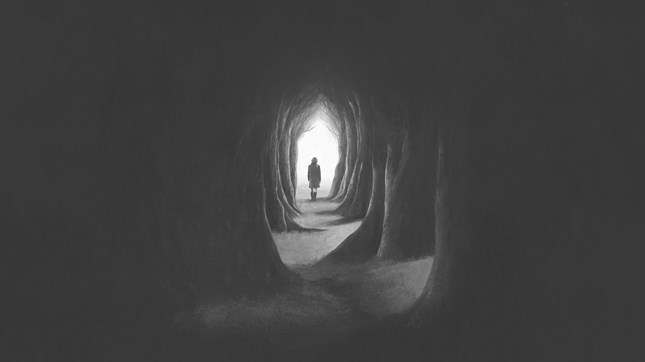

Though I Walk Through the Shadowed Valley

“Different, not less” is how Eustace Grandin describes her young daughter Temple in the award-winning HBO film bearing her name. As depicted in that film, the real-life Temple would grow up to become a renowned animal behaviorist, college professor, and be named one of Time 100’s most influential people in 2010. Temple Grandin is autistic.

Daniel Bowman serves as associate professor of English at Taylor University. In his memoir On the Spectrum: Autism, Faith, and the Gifts of Neurodiversity, he compares the autistic person’s brain to a computer’s operating system (OS). “We have most of the same core features and bugs as anyone else,” Bowman writes. “Our autism is our OS, not a bug.”

One of the challenges to discussing mental health is our reliance on a medical model to assess and describe our own and other people’s mental conditions. To our ears, the word “health” is a measurement of what we believe to be an acceptable, if not optimal, level of capacity and functioning compared to the norm. Mental “illness,” on the other hand, we regard as a sickness, or sub-normality, to be cured.

Healthy eyesight, we say, is 20/20, meaning that we can see what an average (“normal”) person can see on an eye chart from 20 feet away. Healthy hearing we also describe as 20/20, meaning that we can hear like other “normal” people without benefit of aids at 20 decibels in both ears.

But how do we measure mental health? What are the metrics here? What’s normal?

Is IQ an indicator of mental health? Not really. In fact, a 2017 article in the journal Intelligence reported that in one study of Mensa members, whose intelligence ranks in the top two percent of all people, a significant percentage were diagnosed with a mood disorder (26.7%) or anxiety disorder (20%) at some point in their past. That’s more than double the national average of around 10% for each disorder.

Pitzer College researcher Ruth Karpinski who led the study interpreted its findings to suggest a link between high intelligence and psychological and physiological “overexcitabilities.” Rather than being a sign of good health, research shows that a high IQ can come with serious mental and physical problems.

Does Karpinski’s study prove that it’s better to possess “normal” intelligence? Who’s to say what’s normal? Normal compared to whom? My son is a Level 1 autistic adult. He struggles to detect and decode social cues, but he holds a master’s degree in laboratory management from a state university and holds down a full-time job at a local medical lab. His closest friend is an engineer. Is my son “normal”? Is Temple or Daniel? Am I? Are you?

The Folly of Comparisons

Paul writes about the foolishness of comparing ourselves to one another in 2 Corinthians 10:12. The more we learn about how the brain develops in the womb, how early childhood environment influences our perceptions and preferences throughout life, and how numerous other factors affect both our mental traits (that are essentially fixed by nature) and mental states (that fluctuate based on context and stimuli), the more difficult it becomes for us to distinguish mental health from societal preferences. All of us are seemingly wired to judge ourselves and those who think like us as normal and everyone else as weird.

The Enneagram recognizes nine different personality types, each one connected to the ways people think, feel, and engage. No single type can be said to be healthy or normal. Each one just is. All of us process the world in ways that are both similar and dissimilar to everyone else. That makes us different, not less.

We place an unreasonable burden upon ourselves by trying to measure up to how we assume other people think we should think and feel. The more introspective we are, the heavier that burden grows. We would spare ourselves and one another a great deal of mental anguish by stopping the comparisons, accepting ourselves for the thinking and feeling beings that we are, and striving to live gratefully the best version of our lives that we are capable by God’s grace.

What Crises Reveal

Life crises are stimuli that have a direct bearing on a person’s mental state. Catastrophic illness, birth defects, divorce, eviction, unemployment, and the death of a loved one are just a few examples of major life changes that can destabilize us psychologically and/or reveal our deepest convictions.

Consider Job. He lost his wealth, his children, and his health, all in rapid succession. By the time his friends arrived to comfort him, Job was cursing the day of his birth. But through it all—his losses, his suffering, the false accusations, his wife’s advice to curse God and die, his bewilderment over why all this was happening to him, and God’s prolonged silence—he held firmly to his faith. Job’s life crises did not break him. Rather, they proved him to be every bit the “blameless and upright [man] who feared God and turned away from evil” that his neighbors perceived him to be (Job 1:1).

When the Lord trims back our hedges so that people can peer into our backyards, what will they see? When our defenses come down and how we really think comes out, what will they hear? Will it reflect poorly on our Lord, as Satan predicted would be the case with Job (1:9-11)? Or will we like Job and prove the Devil a liar by continuing to trust the Lord and speak rightly of him (42:7)? That answer will be largely determined by how we condition ourselves to think daily (Phil. 4:8).

Crises reveal our true selves. They peel back our masks to disclose our minds. As uncomfortable as that can be, God allows it to happen to us just as surely as he permitted it to happen to Job. When he does, will we like Job and humble ourselves before him and confess his wisdom to be greater than our own (42:1-6), or will we react like Job’s friends who tried to interpret God’s ways according to their own understanding? In the former we find our peace, in the latter our personal undoing.

What Crises Yield

Crises not only reveal our true selves, they remind us by making real to us again many things that happier times cause us to forget or otherwise take for granted. Agur, recognizing the dangers of having both too much and too little, prayed:

Two things I ask of you; deny them not to me before I die: Remove far from me falsehood and lying; give me neither poverty nor riches; feed me with the food that is needful for me, lest I be full and deny you and say, “Who is the LORD?” or lest I be poor and steal and profane the name of my God. (Prov. 30:7-9)

Agur feared the deceptiveness of wealth and woe alike. He recognized that both can cause us to forget who we are before God so that we treat him as either unnecessary or unhelpful in dealing with the real world.

It’s one thing to be able to give the right answers on a classroom quiz but an altogether other thing to be able to apply them in the lab, whether the subject is chemistry or theology.

I was in my final year of doctoral studies when God decided to round out my theological education with a nearly fatal illness. The ordeal began on August 1 with an upset stomach that wouldn’t go away. Six weeks later, my primary care physician diagnosed my problem as stress related. Time would reveal that he was only partially correct.

By mid-November, after dealing with a severe case of ulcers from my mouth down to my gut, I had no choice but to seek out a specialist. It took the gastroenterologist only minutes to diagnose the problem as an immunodeficiency disorder, most likely Crohn’s.

The weeks that followed brought one setback after another. Dehydration, insomnia, various aches and pains, fevers, and weight loss became common. Over four months, I lost nearly 40 of my 175 pounds, resulting in a five-weeks long hospitalization and the loss of another 10 pounds.

The Mayo Clinic studied my labs and agreed with the gastroenterologist. I was suffering from Crohn’s, though they admitted to having never seen a case as aggressive as mine. Meanwhile, I developed a nasty fever from a secondary infection due to the peripherally inserted central catheter cut into my chest.

I would later learn that by that point my chance of survival was less than 25%. There was no time to waste and nothing to do but try to heal the infection then remove my colon, which is precisely what a surgeon did in an emergency procedure on Christmas Eve.

Throughout the weeks of recovery that followed, I tried to make sense of my experience through a collection of short essays that I eventually self-published. Looking back now, twenty-two years later, here in brief are a few of the lessons that my crisis yielded but which I still struggle to apply.

- Stress poorly managed is a major contributor to a host of mental and physical health issues.

- Rushing through life empties it of meaning. I keep forgetting that, in the words of a certain country and western song: “All I really gotta do is live and die. I’m in a hurry and don’t know why.”

- Waiting on God in prayer is far different from saying my prayers and heading off into what’s next.

- The hidden things still belong to God. Mystery is a part of life. I can either rest in faith in his sovereignty or worry myself sick.

- Suffering sensitizes me to the sufferings of others if I let it.

- Family and friends are some of my greatest and least appreciated blessings.

- I don’t think often enough about heaven and hell.

- I am too easily distracted from living in the moment and too quickly forget what God wants me to remember. (This may be the most important lesson of all and key to the rest.)

Conclusion

Mental health is both a trait and a state. As a trait, it is generally fixed by God’s design and affected by Adam’s fall. Like the Gadarene demoniac who was not in his right mind until he sat at Jesus’ feet (Luke 8:35), none of us will be mentally whole this side of glory.

As a state, our mental well-being fluctuates. Just like God often found it necessary to remind Israel of his hand in her past to readjust her perspective, and just as Jesus called upon the churches of Ephesus and Sardis to remember certain things from their past to improve their current states (Rev. 2:5; 3:3), we can find a healing balm in recalling what God has done in our past and in the knowledge that he who began a good work in us will be faithful to complete it in due course.

Healing is different from a cure. Healing is a process that brings relief, strengthens, and enables us to carry forth in something approaching normal. May the Great Physician grant each of us healing now while we await heaven’s final cure.

Gregory Hollifield is the Associate Dean at Memphis College of Urban and Theological Studies at Union University and Book Reviews Editor for the Journal of the Evangelical Homiletics Society.