Skill Builders

Article

Liking the Lectionary

For 17 years I was an expository preacher at a midsized non-denominational church in California; however, after leaving pastoral ministry, I found myself increasingly drawn to liturgy. Though in guest preaching I often delivered expository sermons, on my off Sundays I slipped into a local Episcopal church just to experience the liturgy. Eventually I joined a church plant associated with the Anglican Mission in the Americas and Bishop Todd Hunter. Now I find myself preaching twice a month at that church following the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL). Along the way I am learning valuable lessons about lectionary preaching that build on my experience as an expository preacher.

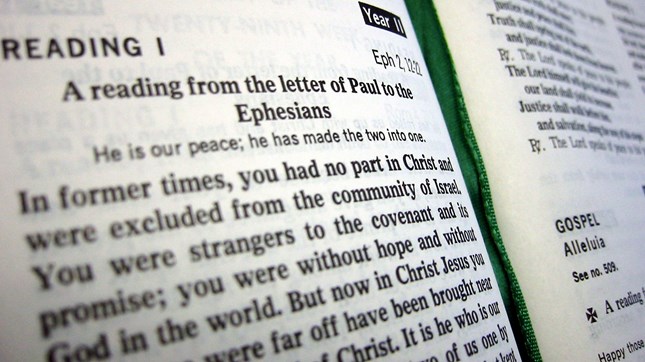

Discovering the Lectionary A lectionary is a book that contains appointed Scripture readings for particular days coinciding with the Christian calendar. According to preaching historian Hughes Old, use of lectionaries originated in synagogues in the fourth century before Christ. By the fourth century after Christ, church leaders had adopted this Jewish practice in Christian worship. Christians have been using lectionaries for a long time.

The RCL is the product of the Consultation on Common Texts (CCT), an interdenominational Christian group that began meeting in 1978. Their first draft was released in 1983 and tested for six years. After considering feedback, the RCL was released in 1992. The RCL is used worldwide by English speaking Anglicans, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Methodists, and many other denominations. Some Baptist and non-denominational churches, as well as non-English speaking churches, also use the RCL.

In addition to providing a daily Bible reading cycle ("daily office"), the RCL assigns four readings (or lessons) for each Sunday: a Psalm, an Old Testament passage (sometimes two), an epistle passage, and a Gospel passage. Year A covers Matthew, the Old Testament patriarchs, and the exodus narrative. Year B covers Mark and the Old Testament monarchy narrative. Year C covers Luke, Israel's divided kingdom, and Old Testament prophets. John is interwoven through all three cycles, especially Year B. Readings from Acts are substituted for the Old Testament lesson during the Easter season. The readings for the season between Pentecost and Advent provide two options for Old Testament lessons. Although the RCL does not include the entire Bible, the CCT committee's intent was for all the voices of Scripture to be heard by the church over the course of three years.

Appreciating Lectionary preaching

There are many aspects of lectionary preaching to appreciate. Foremost is that it roots preaching in the broader Christian story. This is done by correlating each week's readings with the Christian calendar, especially during Advent, Epiphany, Lent, and Easter. Previously in my pastoral ministry, the only seasons I observed were Christmas and Easter. However, more recently I have discovered a new depth in keeping time with the entire Christian calendar. The Christian calendar retells the story of Jesus each year, beginning in Advent with its anticipation of Christ's coming, to Christmas with its emphasis on the incarnation, to Epiphany with its focus on Christ's revelation to the nations, to Lent with its emphasis on Christ's prelude to suffering, to Holy Week with its emphasis on his passion, to Easter with its 50-day emphasis on resurrection, to Ascension with its focus on Christ's exaltation as our high priest, and finally to Pentecost with its focus on Christ sending the gift of the Holy Spirit to empower the Church for mission. The Christian calendar retells the story of Jesus each year.

The RCL assigns readings that are appropriate to each season. For instance, the fourth Sunday of Advent year A assigns the birth account of Jesus from Matthew 1:18-25. Year B has Luke 1:26-38, and year C Luke 1:39-55. Over three years, both nativity accounts are fully heard. On the first Sunday after Epiphany, Year A has Matthew's account of Jesus' baptism, Year B Mark's account, and Year C Luke's account. By coordinating with this calendar, the RCL roots our worship and preaching in the story of Jesus.

Adapting to the rhythms of RCL sermon preparation

Lectionary sermon preparation can be intimidating. Instead of a single passage, the preacher has four passages to study. However, my approach is essentially the same. I analyze the passages to derive my best approximation of each passage's meaning. I use the tools of grammatical analysis, word studies, background study, and commentary work. A helpful source I have discovered is the Feasting on the Word commentary series edited by D. Bartlett and B. B. Taylor (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press). This commentary offers theological, pastoral, exegetical, and homiletical essays on each passage following the RCL calendar.

Another important part of preparation is probing the connections between the passages. The CCT strategically grouped texts together during Advent, Epiphany, Lent, and Easter. Finding the threads that connect these passages enables a preacher to craft sermons that are both biblical and that honor the tapestry of the assigned texts. The CCT intentionally avoids typological reading of the Old Testament; instead, they select Old Testament texts that have a clear connection with the Gospel reading prescribed for the day. In the preface to the RCL, the CCT briefly describes their overall approach to pairing Old Testament and gospel texts.

For example, the third Sunday in Lent in year A assigns a reading from Exodus 17:1-7, a narrative of Israel's testing God in the wilderness because they had no water. Psalm 95 is also assigned, which is a later reflection on Exodus 17:1-7, with the psalmist warning new generations not to be like the Exodus generation. The RCL is filled with these intertextual links for the preacher willing to look for them. Although the CCT doesn't elaborate on their specific reasons for pairing texts, many of these connections are explored in the Feasting on the Word commentaries.

Another kind of connection between passages is a common metaphor. For instance, the third Sunday in Lent of year A lists the following texts: Exodus 17:1-7, Psalm 95, Romans 5:1-11, and John 4:5-42. As previously mentioned, there is an intertextual link between the Exodus and Psalm passages; however, a common metaphor also joins them. Exodus and John both contain narratives about water: in Exodus the water gushing from the rock, and in John the living water offered by Jesus to the Samaritan woman at the well. Similarly, Paul uses a water verb in Romans 5:5, "poured out." Water is a common metaphor that thematically unites these texts.

The CCT does not intertextually pair texts during the season between Pentecost and Advent. Instead, the texts during this season follow a semi-continuous pattern relatively autonomous from each other.

When constructing a lectionary sermon, the preacher must decide how to design it. One strategy is to preach all four texts, spending time on each one and crafting transitional statements that use the textual connections to progress. Another is to select one of the readings, basing the sermon primarily on that text and weaving into that explanation insights gleaned from the other lessons. This is especially appropriate on special days, when one text encapsulates the theme on that particular day. Still another strategy, particularly appropriate for the season between Pentecost and Advent, is to select one section of the reading, such as the patriarchal narrative or the Gospel, and preach continuously through that book each week.

Preaching from the RCL has been a great adventure. It builds on my previous training as an expository preacher by helping me stay rooted in the Christian story. Preaching the RCL also forces me to grapple with texts that I would not normally be drawn to, often finding hidden insights that I would have missed otherwise.

Timothy J. Peck is director of the chapel and a lecturer in the school of theology at Azusa Pacific University, Azusa, California. He preaches regularly at Christ our King Church in Azusa.