Skill Builders

Article

Stories Are for Adults

When we preach, we want those listening to us to learn and apply God's Word to their lives. In order to accomplish this objective with adults, we would be wise to include narrative sermons from the narrative portions of Scripture in our preaching repertoire. How can we preachers ensure that the narrative sermons we preach reach their potential?

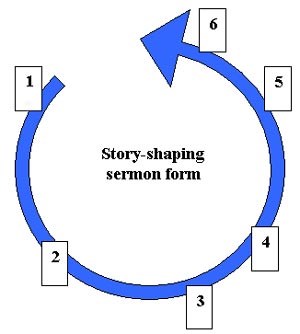

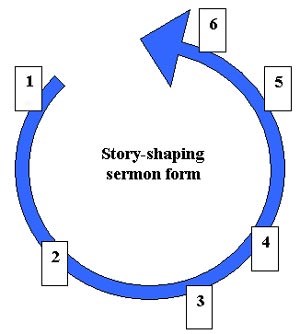

The first step in preaching what I call a story-shaping sermon is to interpret a biblical narrative from a literary perspective. Preachers who do not understand the literary dynamics of how the biblical writer fashioned his story will not understand the theological point he was making, nor how to harness the literary power of the original story in their sermons. While scores of books have been written on the literary dynamics of biblical narrative, perhaps the most important factor is the shape of the story. The mono-mythic cycle is a helpful tool that preachers can use to determine a story's shape.

|

Since conflict is inherently interesting, stories start with an inciting event. Something goes wrong with the summertime perfection we would all prefer. Stories spend most of their time exploring the increasing complications that occur as negative events unfold. As far as the protagonist is concerned, life is getting colder and colder—worse and worse. While a few biblical stories end in winter (these are called tragedies), most don't. The vast majority of biblical narratives enjoy a sudden reversal—a surprising twist in the plot that begins to return life to the bliss of summer. Stories do not have points. They make a single point. This point is revealed in the surprising twist—the moment of "aha" when the solution to the problem is revealed.

The point of a biblical story is always a theological point. We learn something about God and how to live in response to him when we understand a biblical story. The narrative literature of the Bible is concretized theology. The stories of Scripture examine abstract theological truths through the lens of real-life situations. Properly understood, biblical narratives discuss theology in an adult-learner oriented, "case study" approach.

Story-shaping sermons are an attempt to harness the natural advantages of narrative literature for the benefit of the adult listener. As the diagram below indicates, this sermon form shamelessly piggybacks upon the structure of the biblical narrative, while intentionally intertwining the lives of the listeners with the problem faced by the biblical protagonist. If this is done successfully, the problem of the biblical protagonist becomes the problem of the contemporary listener. As a result, the listener looks with interest at the critical choice made by the biblical protagonist to resolve his or her ancient problem—and decides whether to follow the protagonist's example in their contemporary situation.

|

Story shaping is a homiletical attempt to reshape the story of our listener's lives with the lives of the biblical narratives. Here is how it works, in six phases.

1. Personal identification with the biblical characters

Your sermon begins in the summer of the narrative. Your goal in this portion of your sermon is to help your audience identify with the biblical character. Build bridges between the biblical character and your audience. You want your audience to discover the ways in which their lives are linked to the lives of the biblical character. It may be helpful to ask yourself:

• Who is this person?

• Where do they live?

• What is their background, education level, profession, and social standing?

• In what ways are they like my audience?

2. Awareness that characters in stories can and must make choices

As you relate the "fall" difficulties being faced by the biblical character, show the parallel pressures in the life of your congregation. Biblical characters were real people. You want your congregation to feel the same tension and pressure that the biblical hero felt leading up to her or his decision. Harness this pressure to help your audience recognize that we cannot avoid making choices. The following questions will help clarify your thoughts.

• Is the biblical character a victim or a victimizer? Of whom or what?

• Does the character display a sense of powerlessness?

• Have you (or someone you know) ever felt the same way?

Take time to go through the biblical story scene by scene and outline the parallels between the protagonist's story and the life story of the listeners. As you do, be sure to preserve the inherent tension of the story. If there is no tension or conflict in your sermon, there will be no interest. If there is no interest, there will be no life change.

3. Understanding what the biblical character decided and why they made that choice

At this point, you are in the winter of the biblical story. Things have become unbearable and the character has chosen to act. You are at the bottom of the mono-mythic circle, the climax of the emotion. Here you are looking for the biblical character's psychological motivation. What would have made this decision difficult?

|

• When did the character finally choose to act?

• Why not earlier or later?

• What decision did the character make?

• Why did the character finally choose to act?

• What factors motivated the character to act the way that he or she did (social, physical, spiritual, and so on)?

4. Emotional identification with the consequences the biblical character faced

In the fourth phase, the diagram above curves upward. It assumes you are preaching a biblical story with a happy ending. These comedic stories are best used to show audiences how godly decisions result in restored lives.

But while many biblical stories end positively, like Daniel's, this is not universally true. Characters like Samson, Saul, and Absalom did not make God-honoring decisions. The lesson of their lives is negative. We are not to imitate their decisions.

Regardless of whether the biblical narrative you are preaching ends on an up or a down, however, help your congregation slip into the sandals of the biblical character who made the decision. God-honoring decisions have a real and often immediate impact upon the life story of the decision maker. Allow your congregation to see this.

• What happened to the character when the choice was made?

• What happened to those around the character (friends, family, members of the community)?

• Have you ever faced or made a similar decision to the biblical character? Did you face similar consequences? Why?

• Would the consequences experienced by the biblical character likely follow a similar decision today? Why?

5. Deciding whether to emulate or avoid choices made by the biblical characters

|

Let your congregation have a good look at the benefits of God-honoring choices. Allow them to gaze on the ripple effect that those decisions had on their family, friends, and community and then bring them to the point of decision. Exhort your congregation to learn from the mistakes and successes of the heroes of Scripture.

• What is holding you back from making a God-honoring decision today?

• What are the pressures you face to imitate or reject the decision of the biblical character?

• How will your life be changed by your choice?

• How would the stories of others (family, friends, church community) respond to and be affected by your decision to imitate the biblical character?

6. Altering behavior in accordance with the decision

As a caring pastor, you know many of the issues with which the people in your congregation are struggling. Give them specific examples of what the application of this passage might look like in their lives. Concretely outline how their actions might be different as a result of their choice. Challenge them to implement the lessons from this text into their lives immediately and to tell someone about their decision to do so.

The story-shaping sermon form does not make six different points. It proceeds through six stages to make sure the listeners understand the single theological point of the narrative passage, and how that point influences the life story of the listener. As you make your way through the sermon, you will weave in and out of the ancient and modern worlds, explaining the text so that your listeners appreciate the depth of the problem the biblical protagonist faced, and explaining how your listeners will face very similar tensions in their lives. You will be able to stitch these worlds together into a seamless and unified sermon.

Kent Edwards is professor of preaching and leadership, and director of the doctor of ministry program at Biola University in La Mirada, California, and author of Deep Preaching (B&H).