Your Soul

Article

12 Defining Moments: The Moment to Decide

Editor’s Note: If you have missed any articles in this series, be sure to check out the Introduction article, where you can find all of the articles that have been released.

Among the leadership myths many pastors embrace is the myth of the heroic leader, the one called and anointed to single-handedly guide and manage the church. It’s not surprising. Most of us begin in small works. By necessity, we are expected to run the board, take ownership of fiduciary matters, oversee policies and procedures, determine outcomes, preach, pray, and do visitation. Oh, and make the coffee.

Pastoral training does not help. Few resources discuss team building. Graduates enter ministries with the assumption leadership is a solo act rather than a team effort. The result is a low regard for organization and method. Over time, things tend to fall apart. Pastors begin to burn out and congregants become frustrated and weary. Such moments require divine intervention.

Leadership’s Defining Moment

Early into my second pastorate, I was forced to confront my leadership style. Things had turned rocky in my relationship with the chair of the elder board. There were times we stood together, prayed together, and even affirmed our affection for one another. Gradually, however, our day-to-day interactions became contentious. One afternoon the chair of the elder board stopped by church and marched up to my office. I can still hear his accusatory words: “You are the most autocratic leader I have ever met!”

I was flummoxed. Was he having a bad day? Was this some irrational charge by a man insecure in himself? He certainly saw something in my style of leading that was off-putting. Was I trying to be a heroic leader? Had I overstepped my bounds? Did others on the board see me as an independent type, seeking to control the decision-making?

What I knew for certain was that this was a defining moment. I had to decide what kind of leader God summoned me to be.

Maybe your story is similar. Maybe it is yet to be written. Or, perhaps, it is just the opposite. In your case, those on your team have confronted you regarding your failure to step up and lead. Either way, a moment comes when all of us in ministry must grapple with our leadership styles.

Something in our self-oriented nature draws us to be standalone leaders. One advantage is that leading is less cumbersome. Leading with others can impede momentum. Meetings can devolve into paralysis. More directive leadership, free of structured meetings and orderly reports, tends to get things done.

It is true, however, that reducing leadership to oneself stifles the institution. As Max DePree puts it, “Any leader who limits his organization to the talents and time of the leader seriously handicaps the group.” Most leadership responsibilities eventually outdistance the capacities of any single individual. One is too small a number to achieve greatness.

It's also correct to say that the world has become weary of the great man theory of leadership. The heroic, arms crossed, standing proudly in the pulpit pastor is less admired today. The top-down pyramidal hierarchies (high distance leadership) are yesterday’s leadership model. Such styles are also contrary to the models of Scripture.

Trinitarian theology teaches that God takes a team approach to all his endeavors. Father, Son, and Spirit work corporately. It is a relationship of interdependence. The Father collaborates with Jesus (Heb. 1:2; John 5:19); the Spirit works in partnership with the Son (cf. Matt. 4:1); and Jesus builds a team to advance his kingdom (Matt. 4:18-21; John 1:29-51).

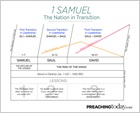

God’s leaders model the same: Moses discovers the folly of going it alone (Ex. 18:17-26; Num. 11:16-24); Nehemiah’s endeavor to build the wall is successful because it is a team effort; and Paul approaches his ministry as a partnership (Titus 1:5-7; cf. Acts 6; Eph. 4:11-12; Rom. 16).

Seven Rules for Effective Collaboration

While there are moments when a leader must have the courage to take a stand, even if it means standing alone, one should, in the main, exercise joint leadership. To do this well requires that one lay hold of the rules of collaboration.

1. Do a Personal and Corporate Assessment

Personal . Building a collaborative framework begins here. Do I see myself as a team player? What is the evidence? Would those who have worked with me in the past regard me as cooperative or independent? Do I tend to be self-reliant and self-contained, or in need of others? Do I use teams to hide behind the decisions I alone must make? What are my inclinations?

Corporate . Am I inheriting a more collaborative or a more standalone culture? If there are teams, are they teams in name only--working groups that are little more than loose agglomerations? Or do I find people with complimentary skills equally committed to a common purpose, pursuing goals for which they hold themselves mutually accountable?

In assessing, I need to determine what organizational configurations need to remain, be modified, or abandoned. What is the performance level of the teams?

Sometimes restructuring is needed. In some cases, there will be godly elders who are not gifted in leadership and gifted leaders who are not godly. Likely I will take over a staff where some will be less collaborative and more independent. I will be asked to work with chairpersons who may not have the right chemistry, or a committee that has long sense served its purpose. How much say do I have in structuring and restructuring, selecting and deselecting?

2. Create an Environment of Interdependence

Given that a legislative approach leads to more effective leadership, it is vital to create and strengthen a community of mutual reliance. This requires a certain humility.

In a context of reciprocal need, monologue is replaced by dialogue. Members come together at the table and recognize “we’re all in this together.” The success of one depends upon the success of the other.

These are churches known for developing cooperative goals and roles. Here leaders and their teams support norms of reciprocity, structure projects to promote joint efforts, and support face-to face interactions.

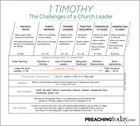

3. Establish Multiple Teams that Complement One Another

An organization is best served by various teams with diverse objectives. This is the conclusion of a Harvard study (see Senior Leadership Teams, Wageman). A healthy church has at least four kinds of leadership teams:

- Information Team: Its primary function is to gather intelligence (e.g. What is the demographic of the community surrounding the church?).

- Consultative Team: One recruited to advise a board on a needed decision (e.g. should the church relocate or upgrade its present site?).

- Coordinating Team: Might be enlisted to coordinate strategy (e.g. putting together logistics for the creation of a second service and the recommended aligning of all the ministries).

- Decision-Making Team: One that makes the necessary calls.

No team is more important than the fourth team. It might be one’s executive committee (comprised of senior elders) or core staff (a smaller group of the broader staff team). These set the agendas, discuss issues requiring greater confidentiality, and make the most significant decisions. Members of these share leadership at the highest level.

In the spirit of collaboration, a pastor might consider creating other teams. In my third church, I created an apostolic group. These were the leaders who were entrepreneur types, those who can recognize the next opportunity. Together we would imagine a more expansive future. It was an exhilarating team. Like the first three, they had no authority, but their input was invaluable (even if their impatience with procedures and policies kept them from volunteering to carry out their ideas!).

4. Instill in Teams a Compelling Purpose

In the best of teams, members believe that what they are doing is consequential. The mission provides the context and drives the energy. One senses urgency and intentionality in the execution of it. These are groups moved by a forceful vision, are committed to the strategic plan to get there, and are willing to be part of the tactics designed to meet outcomes.

Keeping the purpose of the church visible—one that surpasses every other organization on earth—is paramount. What is greater than pursuing truth, responding in worship, loving one another, and reaching lost people? If this does not motivate performance and give team members a sense of fulfillment, then nothing will. The best leaders remind their teams that they are changing the world!

5. Build with the Best

Fulfilling the purpose of God requires finding the right people. Business consultant Jim Collins makes the point that a great vision without great people is irrelevant. The wisdom of God warns that building a team with lesser types can make a mess of collective endeavors (Prov. 10:26; 25:13,19; 26:6,10; 13:20). On the other hand, those who are filled with discernment and prudence and godliness make the difference. Walls are built (e.g. Nehemiah)!

What makes for the right people? Look for those in the church who are self-motivated and self-disciplined. Character in a member is primary. Prudent pastors look for those who have integrity, a solid work ethic, a dedication to God, and a commitment to truth. They have the inner strength to withstand the heat, handle stress, and overcome setbacks—all of which are certain to intersect with ministry.

Extraordinary teams are also comprised of people with the right skills and experience. Among the competencies—those who are skillful in the use of their minds. They can synthesize complex information from divergent sources and extract the implications. They are adept at problem solving. Other skills include communication, the ability to manage resources and time, the capacity to adjust and adapt, the capability to execute, and the competence to measure those things that matter.

The right people are behaviorally unified; they connect and click, even if their ethnicities, age, gender, and background are diverse. In such teams, people feel heard; they also want to hear. They are not inclined to simply represent their own areas of interest; they identify with the whole.

Here are some of the questions I have found most important to ask:

- Are you a team player? What supports this?

- How would your peers describe you?

- What are your three greatest strengths and weaknesses?

- How do you handle pressure? Conflict?

Getting the right people on the bus also includes getting the wrong people off. It could be that their skills no longer match the needs of the team. Maybe they cannot take the task to the next level. In some cases, the unsuitable member is one who no longer fulfills the character qualifications mentioned in 1 Timothy 3.

Over time, some become toxic. Rather than create, they generate mistrust. Such members no longer accept the pastor’s leadership—or anyone else’s. What matters is their agenda. These are what one describes as derailers. Left on the team, they often get things off track.

Congregants have an important voice in selecting teams, but a pastor must ultimately make the call. This is your team! Ignore this at your own risk.

6. Create Dynamics that Enable Teams to Maximize Their Effectiveness

Once the right team is in place, a leader must ensure that teams are properly structured for maximum effectiveness This includes—

Clarifying Roles . In the case of the board, what is the distinction between the roles a pastor and a board chair carry out? What does it mean to be the first among equals? Amongst the staff, what differentiates a lead pastor from other pastoral roles?

Defining Responsibilities. Are each member’s duties well defined? Is there an overlap? Unnecessary redundancy? Where could there be potential conflict?

Establishing Procedures. What are the ground rules regarding meetings? Who sets the agenda? If not Roberts Rules, how are meetings governed and decisions made? Does consensus have to be reached? Without answers to these questions, teams can become undisciplined and ineffective.

Developing Norms . There will be tense moments and disagreements. There will be personalities that might rub, even grate, on one another. I have learned that securing behavioral standards together reigns in potential misbehaviors. Establishing boundaries and embracing a code that everyone agrees to is critical. Otherwise, collaboration will be undermined.

Determining Number . Teams have a propensity to be too large. Special groups and family tribes often jockey to be selected so that interests might be represented. This tends to impede successful decision making. The bigger the team the greater the tendency for members to give opinions rather than probe for understanding. Meetings become interminable and consensus may take months. Five to eight is an ideal size.

Discerning Placement. A culture of collaboration involves leveraging the full range of one another’s capabilities. A wise leader places people in their sweet spot, where their strengths best converge with the need. This includes putting your best people in the greatest opportunities—not your biggest problems. Great leaders take the human capital—the most important asset of any institution—and make it more valuable for tomorrow’s world.

Committing to Outcomes. Patrick Lencioni’s The Five Dysfunctions of a Team should be required reading. Boards and staff that maximize their effectiveness and achieve their goals build trust, master conflict, achieve commitment, embrace accountability, and focus on results. In the end, the measure of a great team is whether it has accomplished what it set out to accomplish.

7. Provide the Necessary Resources

Teams can have the right purpose and the right people sitting in the right seats and yet be stuck at the gate. Staff and board need the means to carry out the mission.

This is a challenge, especially for ministries. Most tend to be underfunded and under resourced, and this can be discouraging. In a collaborative environment, leaders come together to fight for the means to do what they have been summoned to accomplish.

Part of the necessary capital includes timely coaching and provisions for retreats that renew and train teams to go to the next level. Teamwork is often difficult and time consuming. Boards can become high-demand, low-stroke environments; decision making is often unnerving.

Wise leaders, those devoted to their teams, go out of their way to make sure teams have what is necessary.

Conclusion

It’s necessary to listen for those moments when God calls us to examine our leadership styles. Leadership can be lonely. There will be times the circumstances demand we go it alone. And God will confirm this. Collaborative leadership does not apply to every situation. In certain cases, executive leadership is the proper approach.

In other moments—most moments—a leader who bypasses one’s team can make a significant misjudgment. When one is committed to collaborative leadership, there is a greater potential for extraordinary ministry. Teams, as one put it, are like audio amplifiers; whatever passes through comes out louder—like Mozart in surround sound.

Chester Nimitz serves as a centering example. He led operations in the Pacific during World War Two. In Nimitz at War, author Craig Symonds states that Admiral Nimitz’s success was due to his courage to stand alone and decide. At critical moments, he was as bold as any commander in the war. In most instances, however, he believed ultimate success depends upon accommodation, nurturing available human resources, and endowing them with authority, responsibility, and freedom of initiative.

It is a leadership template more relevant than ever. Are we listening?

John E. Johnson is an adjunct professor of Pastoral Theology and Leadership at Western Seminary in Portland, OR. He has served as a lead pastor for thirty five years, and currently is a writer working on his fourth book, as well as serving as an interim teaching pastor.